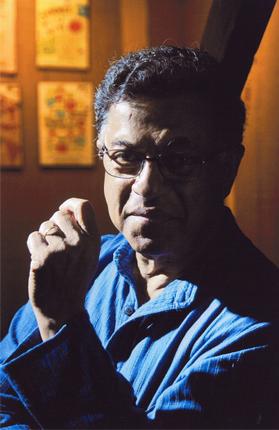

Girish Karnad, one of the key figures in modern Indian theatre, is 75 today. In this interview, he talks about his multifaceted career, resisting the temptation to write like Beckett, and his latest play, based on Bangalore’s debt to boiled beans.

Late last year, after spending six months on numerous drafts and rewrites, Girish Karnad’s new play in Kannada, Benda Kalu on Toast, was ready. The title is a reference to the founding myth of Bangalore, in which an 11th century king was saved by an old woman who offered him boiled beans. The grateful king offered to name the spot Bendakalooru or the place of boiled beans, which, over time, became Bangalore. Alongside this fact, in the preface, Karnad gives us a sense of the sprightly humour we can expect to find in the play. He tells us: “Toast is a strictly western import into Indian cuisine.”

This is a masterfully structured play that makes the city of Bangalore and its explosive growth in the last two decades its subject — though any easy message is withheld. It avoids the prevalent clichés of its image as an IT city or a city of numerous call centres. Instead, it presents the stories of a cross section of those who live in Bangalore, and whose expectations, survival techniques and disappointments are all coloured by it. There are some stories that Karnad does not even seek to close, leaving us uncomfortably aware of — yet riveted by — a sense of incompleteness. Although it is largely realist, the play is not exclusively so and leans on the approaches of post-modern experimental theatre too, producing an effect of ambivalence and distance from the plot points even while remaining engaged with the particulars of each of its 22-odd characters. The Kannada play was quickly translated into English by Karnad, who, with Vijay Tendulkar, Badal Sircar, Mohan Rakesh, is among the four great playwrights of modern Indian theatre.

What followed was a set of exchanges harking back to the heady days of the 1960s and 1970s. This was a time when varied plays were being written and staged in different parts of the country, with exciting linguistic manoeuvres and transfers from one region to another.

The Pune-based Marathi playwright Satish Alekar heard Karnad describe the new play when the two were on a visit to Delhi late last year. He felt immediately that it could be staged by theatre director Mohit Takalkar and his Pune-based group Aasakta, active in the Marathi experimental theatre space. On his return to Pune, he spoke to Takalkar about the new play, adding that it was his kind of play. Intrigued, Takalkar wrote to Karnad, who sent him the English translation. After a meeting in Bangalore, the Marathi translation of the play by Pradeep Vaidya was ready, along with the cast (brought down from 22 to 19). Two months after rehearsals, a sparkling production of the Marathi play, Uney Purey Sheher Ek (One City, give or take some), was warmly received at Pune’s Vinod Doshi Theatre Festival, and a few weeks later at the NCPA in Mumbai. As Alekar points out, the play is quite a departure for Karnad, who has in recent times given up historic-mythic themes and opted for a more direct and realistic gaze at contemporary India. “It takes note of the dissatisfactions, the search for completeness that people in the post-liberalisation development boom have to contend with”, says Alekar.

The Marathi version of the play is a pitch-perfect transfer of the narrative from Bangalore to Pune, with very minor changes. Both cities are similar. They were originally small sleepy towns that were suddenly thrust into a phase of unmanageable growth. Karnad points out that the play can speak for cities like Hyderabad, Ahmedabad and Chandigarh too. It is also a fine achievement of stagecraft and set design. Takalkar’s idea for the multiple-location play was a spare stage with only a shifting set of three blinds. The blind in the centre helped by the light design morphs from a door to a hut, a backdrop to a barista, the reception of a Wipro office to the race course. The play’s meaning and purpose are not always within easy grasp. Says Takalkar, “This combination of contemporary concerns with a classical structure is not something I had seen before.”

***

Karnad, who turns 75 today, has written plays for over 50 years — his first play, Yayati (1961), was famously written on his way to Oxford. He says that structuring and crafting a play is something he cannot help. “It is like being trained in classical music. The besur is excluded even if I want to make use of it to some extent. Which may actually be a weakness rather than a strength in one’s development.”

The inspiration for Benda Kalu on Toast is Sudraka’s great Sanskrit work Mrchhkatika, which also inspired his film Utsav (1984). He was, he says, “interested in capturing this sense of parallel things happening, where narratives impinge on each other but then they move on”.

He presents a finely reasoned argument, with a critical sense of history, in choosing to write a modern play on Bangalore. Unlike Bengali or Marathi literature of the last 150 years, where Kolkata or Pune is always present in the writer’s imagination, Bangalore remains a small town located in a state that was formed in 1956 by stitching together four separate regions with distinct histories. There has been no generation, yet, of writers who were born and brought up here. “People like UR Ananthamurthy and me or Chandrashekhara Kambara all came from small towns. We all carry the baggage of the countryside. No one seems to be able to relate to what’s happening in the city. And meanwhile the city has exploded to an unimaginable extent in the last 20 years. That is why I said to myself that I must write a play about the city and see what it means to me.”

Although he says he is not interested in a play that seems to draw from the day’s headlines, Benda Kalu on Toast is a finely judged and subtle play about all that is wrong with the way we live and organise ourselves, particularly the way we treat our underclass, the migrants and the urban poor. The structure and the coolly dispassionate tone avoid the clichés of traditional leftist, activist modes of critiques. Neither is there nostalgia nor sentimentality or the judging of one group’s needs against those of another. It is impossible to get away without a deeply felt restlessness in response to the varied characters we see and the ways in which they are affected by an impersonally growing city. The hint of hysteria just below the surface is inescapable and perhaps more potent than a direct appeal to our tired sense of right and wrong.

***

Karnad’s career is a testament to his great appetite for life, work and new directions. As a playwright, film actor, filmmaker, translator, screenwriter and arts administrator, he has been able to use his many interests to complement each other. For instance, his work as a playwright has benefited from his work as an actor in films. Unlike other playwrights who remained very word-oriented, his constant work as an actor in parallel and mainstream Hindi and Kannada films has helped him stay in touch with natya, the element of pure performance. Engaging with the arts in different ways has also given him a critical perspective and distance towards his material. After Yayati he wrote Tughlaq (1964), which was received as an allegory about the mistakes of well-meaning Nehruvian socialism. Karnad says he wrote the play because Kannada critic Kirtinath Kurtakoti said there were no historical plays being written.

His next play, Hayavadana (1971), was a reworking of a myth from the Kathasaritsagar exploring the themes of identity and desire. Nagamandala (1988) was followed by another historical play,Taledanda (1990), on the rise of the reform movement Veerashaivism against the backdrop of the Mandir Masjid issue of the times. After Agni Mattu Male (1994), Karnad trained his gaze on more direct ways to aspects of a changing India in the post-liberalisation era with A Heap of Broken Images(2006), written for and performed by Arundhati Nag, and Maduve Album (Wedding Album) in 2009.

“The first great play to me is Dharamvir Bharati’s Andha Yug (1954),” says Karnad. “This is a play that you can say to the world is one of our best. And then came the onrush of Mohan Rakesh, Vijay Tendulkar, Badal Sircar, and I was part of it.” It was a time when the need to create a new dramatic tradition for a modern Indian theatre was keenly felt. Apart from the commercial company nataks, Indian audiences had grown used to actors improvising texts in traditional performances like the Yakshagana. This kept him from writing imitative absurdist texts for Indian audiences. “I have always resisted the temptation to write like Beckett,” he says firmly. In a lighter vein, he talks about the time Mohan Rakesh and he found themselves in Kolkata in 1968 watching a terrible Bengali musical play, which made them laugh. At one point Rakesh turned to him to remind him that they were laughing because the future of Indian theatre was in their hands. “We did really feel that. We were the first generation of really serious playwrights,” says Karnad.

***

On his return from Oxford in 1963, Karnad joined the OUP in Chennai and remained there for seven years and learnt the basics of theatre from his time with the Madras Players. This is when the many sides of his career began to emerge. Reading UR Ananthamurthy’s Samskara, he was instantly jealous he had not written it himself, and the subsequent film whose script he wrote and acted in was made for under Rs. 1,00,000, with his OUP office car serving as his production vehicle.

Karnad’s film roles cover a great range — the understanding husband in Swami (1977) , the idealist Dr. Rao (based on Dr. Verghese Kurien of Amul) disseminating the tenets of the cooperative movement inManthan (1976), the distraught village schoolteacher whose wife is raped by the landlord’s sons inNishant (1975), and the self-centred lawyer of Umbartha (1982). Along with actors like Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil, Mohan Agashe, Naseeruddin Shah and Om Puri, Karnad helped a generation of Indians growing up in the 1970s and early 1980s construct a living image of themselves and their times, in contrast to the escapist fare churned out by the Bollywood machinery.

In conversation, though, he keeps returning to theatre. Tracing the origins of modern Indian theatre, Karnad points out that he has always been drawn more to Chekhov than Ibsen. Yet it is Ibsen — with the social-problem play, the prototypes and the ease of staging offered by his drawing room dramas — who has been a clear favourite in India. It is telling that Chekhov — who is more subtle, whose plays lack a strong narrative and are more performance-oriented, who does not deal with issues, and who cannot be read as one would read a Kalidasa or a Shakespeare — has largely been ignored by Indian theatre.

The absence today of new and varied theatre texts is worrying. Many younger groups and writers have started to devise performances drawing from workshop improvisations and research notes on the lines of verbatim theatre. But while these collaborations may throw up a well-crafted play, the process does not really help an individual writer develop his craft and chart his own progress over years. Karnad refers to Marathi theatre as the only one with a continuous tradition of writing and performance. The picture looks grim almost everywhere else. “All talent seems to have migrated to television, leaving little talent or energy to explore the writing of new texts on a concerted basis,” he says.

Typically, Karnad is already thinking about his next play. It will probably take off from the one character in his new play that seems underwritten and whose world of alternate rock music is something he is not entirely comfortable with yet — a musical play on the lines of AR Rahman’s type of music. At 75, he is ready for a new set of challenges.

~ The Hindu

May 18, 2013