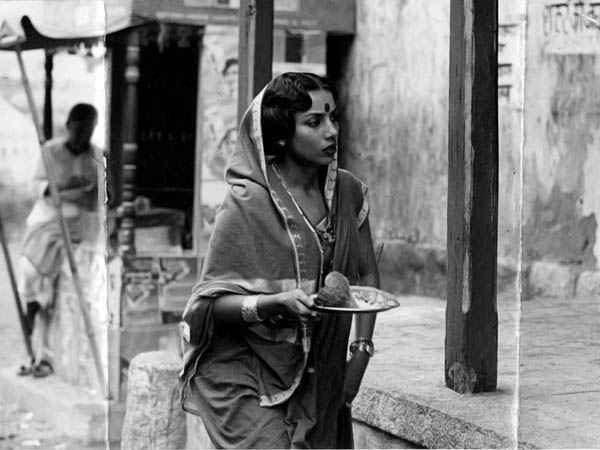

New Delhi: “People interest me. No – that is not the truth. Most people interest me. I follow their lives.” Kumari, choric narrator of Nambisan’s seventh novel, is a retired sex worker who now lives in a corner room of the local temple in small town Pingakshi. Kumari’s sexual adventures have been varied and spirited, many of her clients generous in their own way, willing to indulge her unusual whims.

The doctor whom she cajoles into accepting her services gratis in return for teaching her “some magic with words”, the army man who told her about his travels, even the temple priest who gave her the room she lives in after she became his “weekly habit” have all made her the woman she is – insightful, humane, a practical, non-judgmental spectator of Pingakshi’s comédie humaine.

It is hardly surprising that such an atypical, ubiquitous narrator’s account borders on the bizarre. Beginning with “the gentler story” (a misnomer as it turns out) of Manohar and his encounter with the weeping Saroja in an Udipi café, the narrative takes off in several dizzying directions. Though the encounter arouses Manohar’s interest in Saroja’s life, it does not trigger off the romance one would expect, for he is devotedly in love with his fiercely independent wife Kripa from whom he is temporarily separated. Saroja’s story reveals her in phases: a young bride married to a simpleton whom she eventually strangles and drowns to save her own life; a spirited mother with a five-year-old son, who moves in with the local taxi-driver Sampathu and his “daughter” Rukma; and paramour of the erstwhile temple priest and now small town entrepreneur Devaraya. She effortlessly merges these multiple avatars, the last being born of the practical hope that Devaraya will loan her money to build her dream home.

Kumari’s narration follows all the twists and turns of the roads down which the other residents of Pingakshi meander. Her own life has taught her that a sex worker can hold on to values, dignity and the freedom of choice in the services she will or will not provide. It has allowed her to look into the minds of men and deconstruct the dubious foundations of human altruism. Her choric essence allows her to weave together the present, past and the future and her observations are wry, gently satiric, self-deprecatory at times, and, in their own way, suspenseful.

Kumari can exhort a newly-arrived traveller to relieve himself behind a wall: “Ask not why a wall is built and then left to crumble over the years; ask only that you be permitted to stand facing it with your elbows loosely flexed, your index finger and thumb doing the manly duty learned in early childhood, which is to direct your mictuary arc at a specific spot.” She adds that it is her doctor client who has enriched her vocabulary, teaching her “words like mictuary in a language I do not speak” – an education that allows her some delightfully extravagant forays into semantics: Mention the word ‘latrine’ to anyone, even a Malayali or a Tamil or someone from a faraway place like Kashmir or England and you will get a nod of comprehension. We could do with a bellyful of such words, so everyone understands without having to learn another language. Words travel very well through the length and breadth of our country… A shartu in Kannada becomes satte in Tamil, shart in Hindi and shirt in English. Batlu becomes battl, bothal and then bottle, singal changes to signal… and pup… is a puff for those who speak English which is not at all a difficult language if you see how they have pinched words from our own Kannada. Like medum and saar…

But Pingakshi has its darker aspects, the most prominent being the generation of white-haired infant and children that begin to people it as unchallenged industrial pollution takes its toll. Kumari’s life has taught her the value of competition, something that begins to dominate nearly every character in the novel. Manohar and Kripa are soon engaged in a fierce combat of egos as his creative writing keeps pace with her art, their perverted representation hinting at conflicts that have been dangerously internalised. Saroja’s need to move up in life makes her cheat on the man who has accepted her unquestioningly. The local philanderer Ghulam Bhai, aka “Lectric Mamu” courtesy his profession, cannot accept Saroja’s rejection of his overtures, with disastrous results.

Nambisan’s town and its people have a refreshing rootedness that is enhanced by her sensitive eye for detail and her gentle humour and irony, with their occasional breakouts into the burlesque. Her depiction universalises and de-regionalises Pingakshi, giving it the familiarity of any small Indian mofussil town. Despite the somewhat macabre direction the story takes, it does not diminish one’s overall sense of permanence and sanity.

The problem (if it can be called that) is really the problem of plenty. The quirkiness that initially entices the reader into Kumari’s world is not always sustained. Her choric utterances begin to sink into the reminiscences of an old crone, interrupting the narrative flow and vitiating its suspense quotient. There is a feeling of déjà vu in places, not all the digressions work, and the absence of a tighter balance between oral narration and narrative structure somewhat reduce the impact of an otherwise riveting novel.