What a tantalizing week it’s been for organic chemistry on Mars. We learned that NASA’s Curiosity rover measured a tenfold spike in methane, an organic chemical, in the atmosphere around it and detected other organic molecules in a rock-powder sample collected by its drill.

Scatalogical references to the contrary, methane is a colorless and odorless gas. While it’s a component of both human and bovine flatulence, what gives human “gas” its odor are sulfur compounds, principally hydrogen sulfide and methyl mercaptan, which by the way we share with skunks.

But I digress.

“This temporary increase in methane — sharply up and then back down — tells us there must be some relatively localized source,” said Sushil Atreya of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and Curiosity rover science team. “There are many possible sources, biological or nonbiological, such as interaction of water and rock.”

The sudden increase and decrease immediately gets the heart palpitating. Sure sounds like the work of a living being, but methane, a simple organic molecule made of one carbon atom festooned by four hydrogen atoms, can be created in a number of ways. Bacteria make methane by combining carbon dioxide and hydrogen, and the energy liberated in the process powers their minute lives.

Chemical reactions between water and the minerals olivine and pyroxene in rock also release methane, as does the action of ultraviolet light from the sun on organic materials like comet dust and other meteoric material on Mars. Whether manufactured through living or nonliving processes, methane generated underground can become trapped within the crystal structure of water to form a curious substance called clathrate, a form of methane ice.

Meteor impacts, faults or cracks in the Martian crust and simple outgassing can then release methane at a later date. Earth has abundant methane clathrates buried beneath deep ocean sediments and stored in permafrost. We hope it stays there. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas that already plays a role in climate change. Unlike chocolate, more of it isn’t a good thing.

Because Mars is a windy planet, any methane released is likely to quickly thin out and be dispersed. Methane can be removed from the atmosphere through “photochemistry” or the sunlight’s UV light sparking chemical reactions among molecules. These reactions can oxidize the methane, through intermediary chemicals such as formaldehyde and methanol, into carbon dioxide, the predominant ingredient in Mars’ atmosphere.

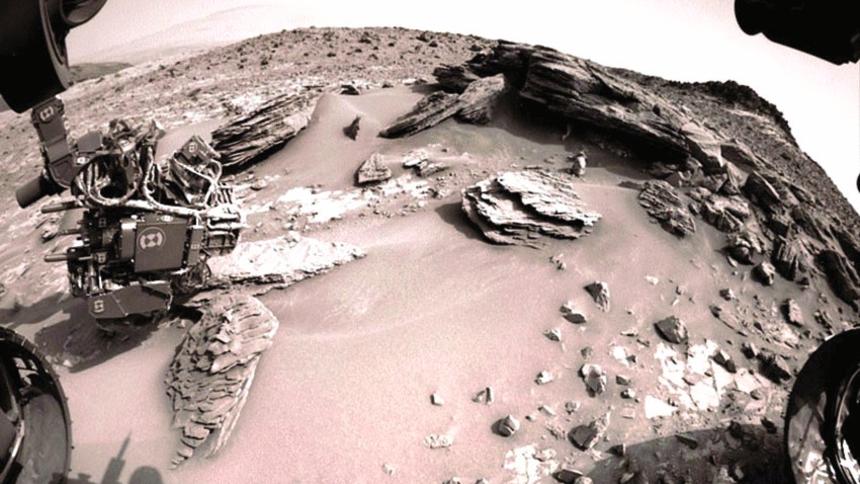

Researchers used Curiosity’s onboard Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) laboratory a dozen times in a 20-month period to sniff methane in the atmosphere. During two of those months, in late 2013 and early 2014, four measurements averaged seven parts per billion. Before and after that, readings averaged only one-tenth that level.

Whatever its origin, we’re not talking much gas — Earth’s atmosphere, of which methane is a minor constituent, averages 1,800 parts per billion. Cattle belching alone accounts for 1 percent of that total.

Curiosity also detected different Martian organic chemicals in powder drilled from a rock dubbed Cumberland, the first definitive detection of organics in surface materials of Mars. These Martian organics could either have formed on Mars or been delivered to Mars by meteorites.

As we saw with methane, organic or carbon-containing materials aren’t necessarily an indicator of little green bugs. They can form and be left in rocks through inorganic processes, too. There’s simply no way to know from the Curiosity data how they originated, but they do give us hope that Mars was once (and may still be) a planet favorable to life.

Identifying which specific Martian organics are in the rock is complicated by the presence of perchlorate minerals in Martian rocks and soils. Perchlorates are toxic salts used for propellants here on Earth because they have explosive properties. When heated inside SAM, the perchlorates alter the structures of the organic compounds, masking the identities of the organics in the sample.

Curiosity also revealed some interesting news about the past water in the Martian atmosphere. According to its measurements, the Cumberland rock formed 3.9 billion to 4.6 billion years ago and contains just half the ratio in water vapor in today’s Martian atmosphere. This suggests that much of the planet’s water loss occurred since that rock formed.

On the other hand, the ratio is about three times higher than that estimated in the original water supply of Mars. This suggests much of Mars’ original water was lost before the rock formed. More information please!

Additional samples, along with data from the NASA’s MAVEN mission, which is conducting a study of the planet’s atmosphere to determine where both the water and air disappeared to, will hopefully give us a clearer picture of the Red Planet’s evolution from a water world like Earth to the present cold, dry desert.

In more recent news, NASA and an international team of planetary scientists have found evidence in meteorites on Earth that indicates Mars had yet another global reservoir of water or ice near its surface.